Cate McQuaid: Ocean in a Drop | Sophia Ainslie on crafting “Woven 12” and “Woven 13” at Gallery NAGA

September 9, 2025

By Cate McQuid

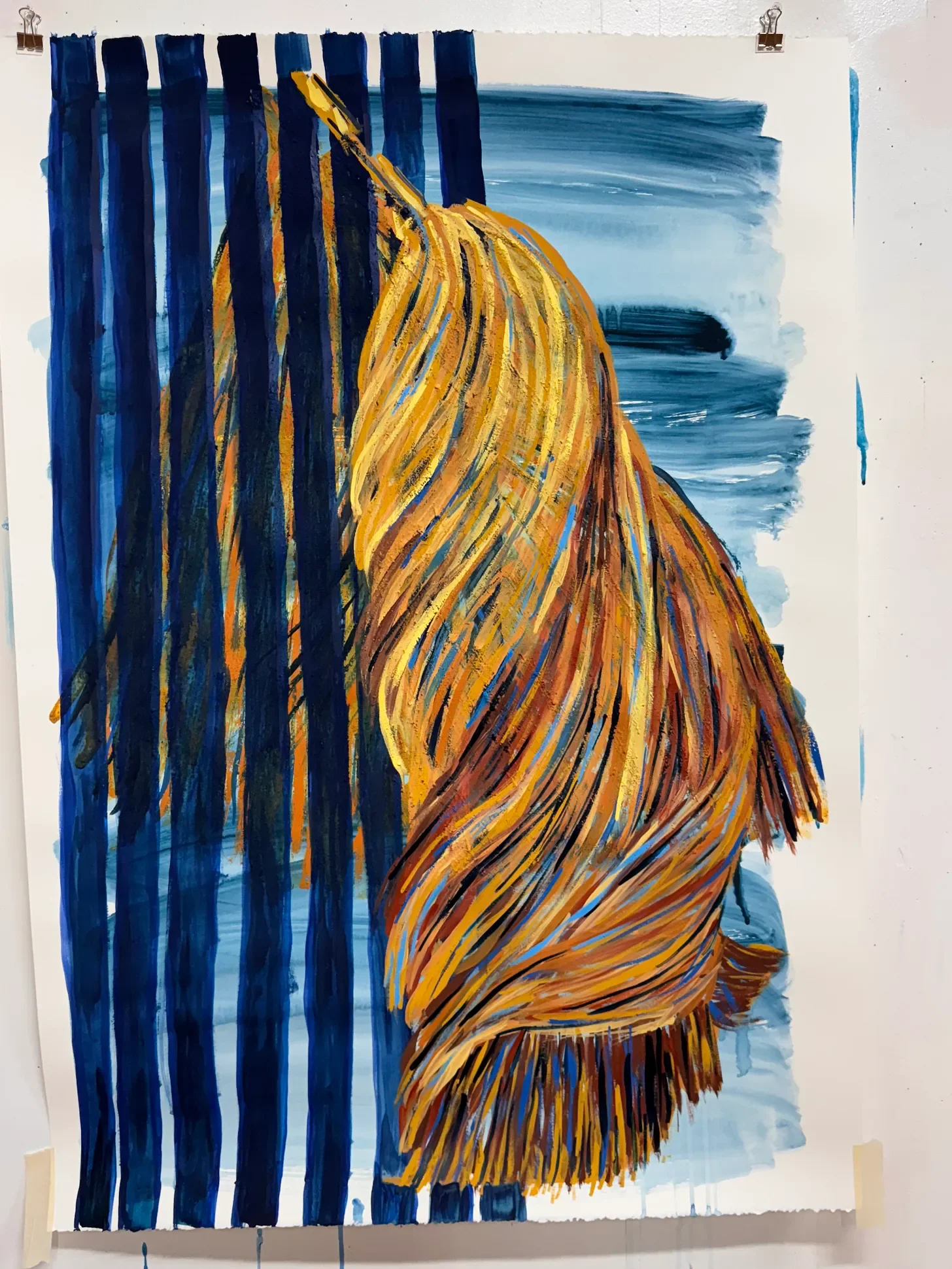

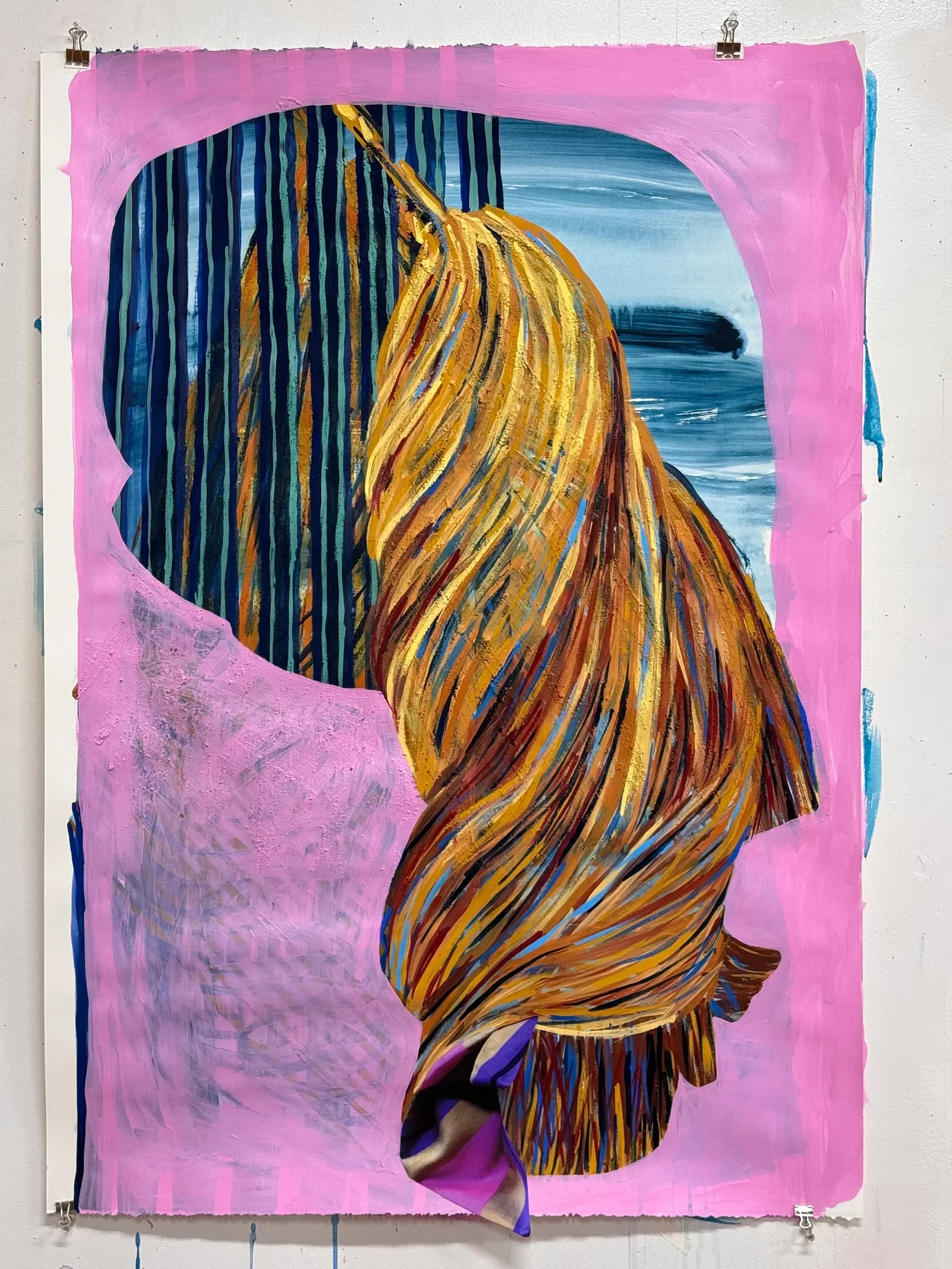

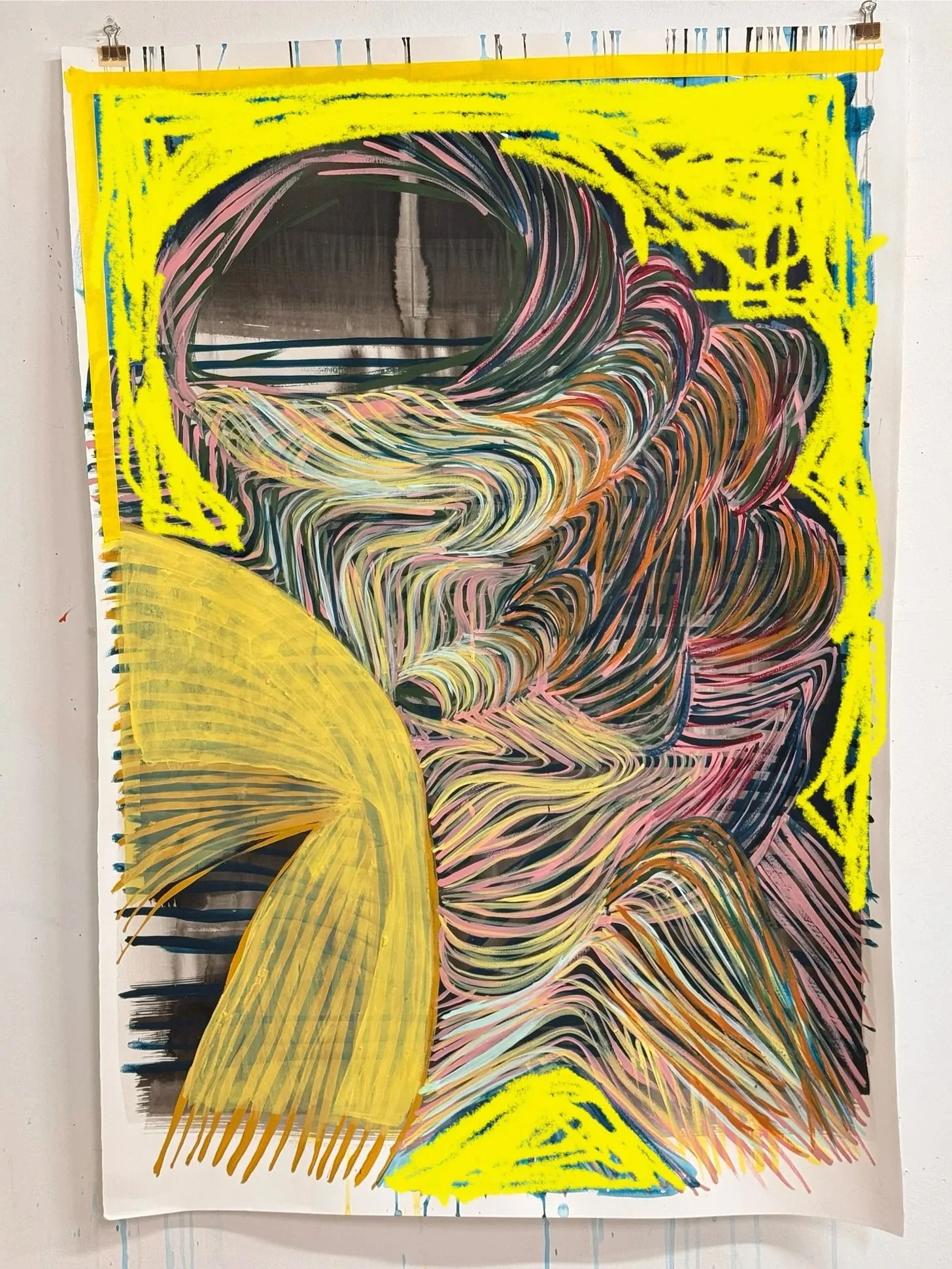

Sophia Ainslie, Woven 13. Flashe paint, sand and archival digital print on paper. 38.25x 27”. 2025. Photo Julia Featheringill.

“Artists, what happens when creativity leaves? How do you manage blocks?”

I posted that question on social media in July, 2024.

“This question comes at a serendipitous moment,” wrote Sophia Ainslie. “I’m there right now, standing in front of a huge creative block. … But I’m in a magical environment (west coast of Ireland) and my studio is faithfully waiting. I know I have been here – lost – before and just need to begin. …I’ve filled my studio with stuff–things I find, like wire, tools, rocks, I’ve printed out images on xerox paper and a large format printer. I’ve gathered other people’s thrown out paint, inks, tools. Then I hung up 8 sheets of 2’x3’ paper that I’m putting paint onto without judgment. One layer each paper. Then another layer in each paper. I’m trying to be in the moment. I’m trying to have faith in process, I’m using my body, mixing colors, applying paint in new ways. Every day I come and look, maybe cut, and make marks. I’m giving myself time and remembering wise words from a South African man I once met out in the wilderness when I was all alone. I asked him, ‘But what happens if I get lost?’ He looked at me with such confusion and responded, ‘How can you be lost? You will always be here.’”

Sophia found her way to the mysterious here, and the fruit of those efforts are now on display in her painting show Woven at Gallery NAGA through Sept. 27. I haven’t yet seen the exhibition, but I know it’s a leap from her last extensive body of work around medical imaging. A relentless search for the intersection of taut formal tensions and the nebulousness of the deep unknown seems always at the center of her practice.

Below, Sophia describes her sources – weather, natural patterns, bodily experience, archival prints of meaningful artifacts, premixed paints – all of which she tosses into what she calls “the compost of my being.” She follows that with patience and tinkering as she waits to see what springs from the rich loam of that compost. The tinkering involves an eye for those formal tensions, a search for problems to complicate the imagery, and a practice of dislocation and relocation that reflects her innate sense, as an immigrant from South Africa, of the unseen imprints of movement.

Maybe she calls these works “Woven” because there’s so much happenstance, wisdom, and compost knotted into their tapestries – or maybe because, looping and flowing with skeins of color, they seem to nod to textiles. Either way, Sophia’s paintings become imprints of her own unseen movements: the questions of new environments and new bodies of work, the resolutions of familiar materials and practices, the ongoing dance between the material and the unknown.

Sophia writes:

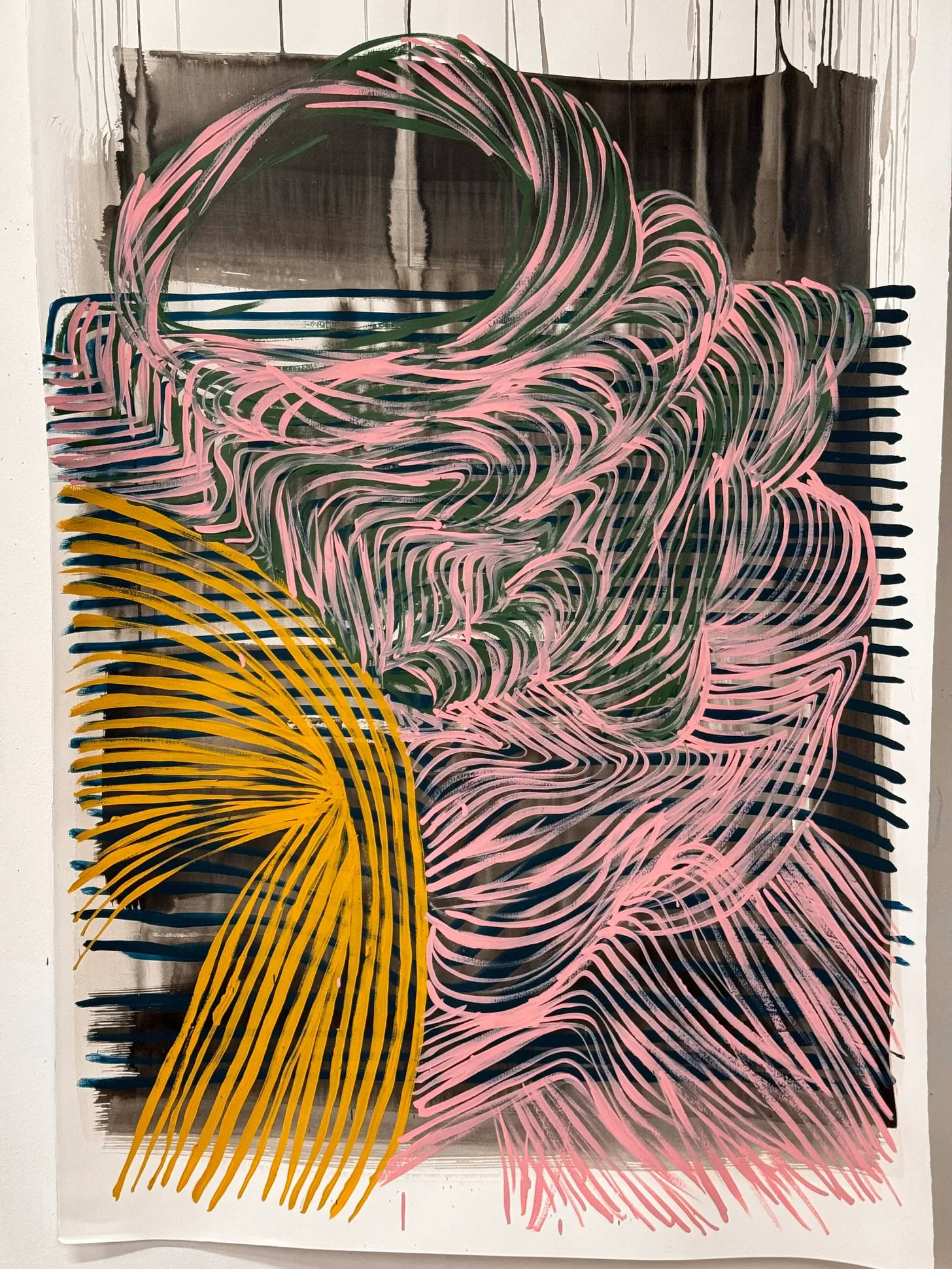

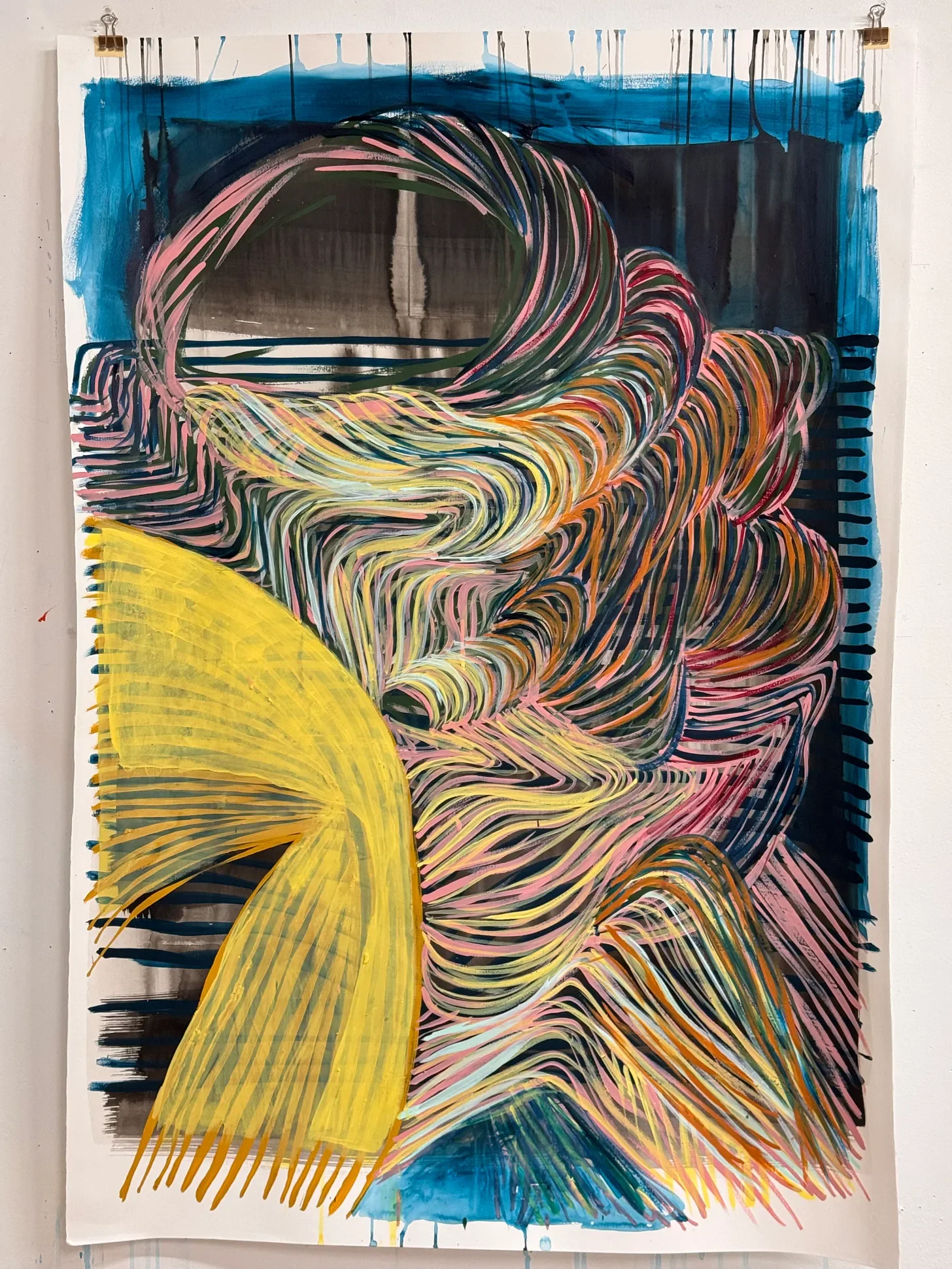

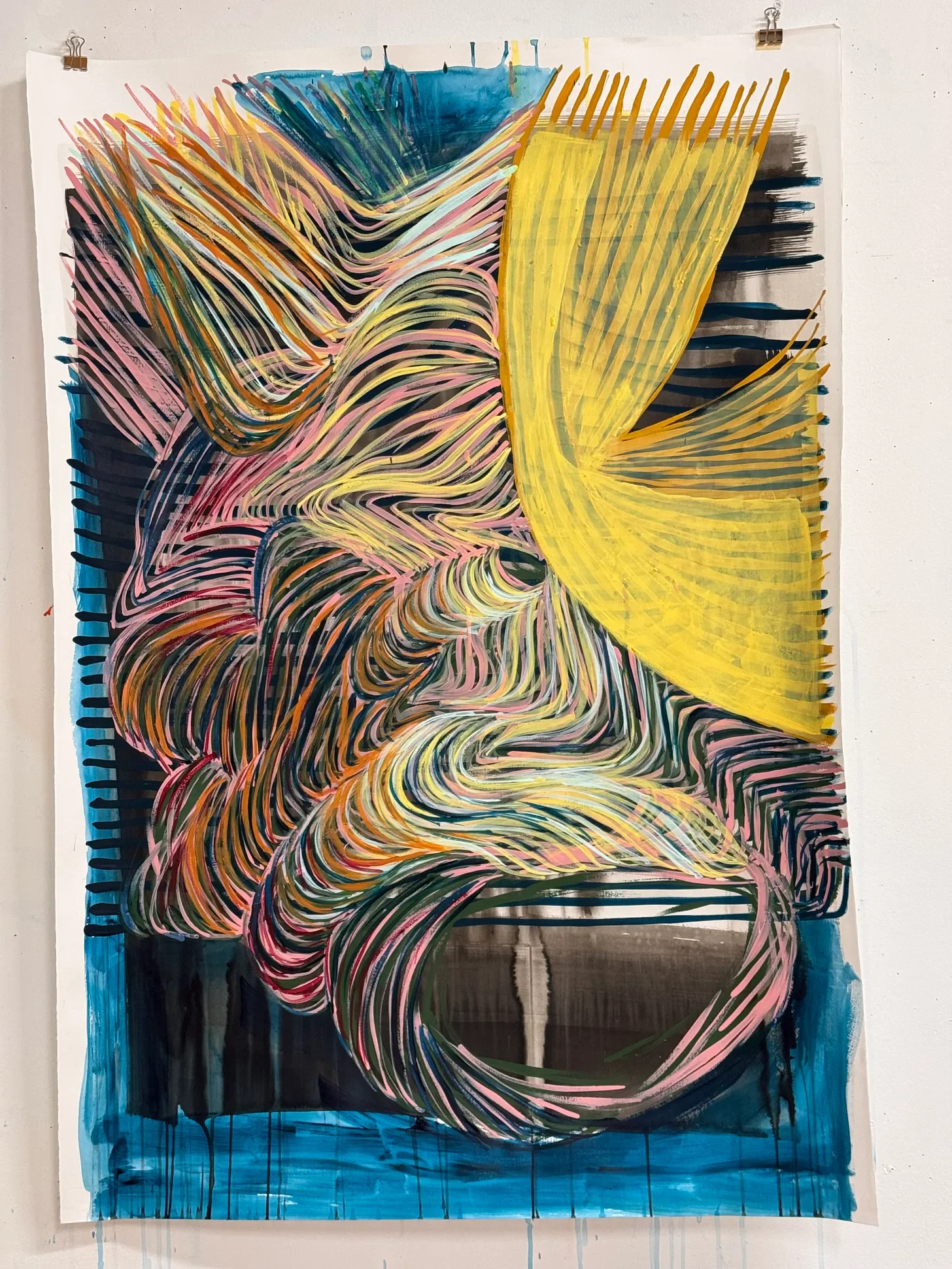

Sophia Ainsle, Woven 12. Acrylic, Flashe paint, India ink and archival digital print on paper. 39.25x27.5”. 2025. Photo Julia Featheringill.

I find it hard to talk about the present without talking a little about the past and where things started. I've selected two works because I always work on more than one. This helps me resolve problems and keep moving. Woven 12 and 13 are part of a series of paintings whose roots trace back to Ireland, where I taught and painted in the summer of 2024. Before that, I had been working with diagnostic imaging as my subject for nearly 15 years. I needed a new departure point and wanted to use my body differently and add more space and dimension. Being in a new landscape, away from the familiar, helped push this shift.

While in Ireland, I noticed the ‘footsteps’ of the wind on the sand, the water, and in the grass, the fleeting patterns of motion and change, and the games the wind played with my hair. I looked closely at the amoeba-shaped limestone rocks etched by acid rain, the spaces between the farmers’ hand-built walls, the glistening sea light, and the feeling of the ever-changing weather wrapping around my body. In the studio, I translated this into paint. The painting process became a stream of consciousness, images surfacing from deep within rather than from something I could consciously plan. I turned off my critical brain.

Back in Boston, I continued this journey. The different landscape shifted the content and color, but the underlying approach remained the same. I began by pinning up multiple sheets of paper, all the same scale: 38.25” x 27”, the exact size of the paper I bought in Ireland. I wanted to keep working on this scale to learn to fully understand “the playground”, the new boundaries of my space.

I start by pinning multiple papers across all my walls. Woven 12 is first right. Woven 13 is 3rd right.

I premixed some of my color (I never use paint straight from the tube). Altering color makes it personal to me. Premixing colors allows me to work swiftly and uninterruptedly. But I also mix color along the way. I work with Golden acrylics and Flashe paint. Occasionally, I mix beach sand into the paint, grounding the work in physical place and adding texture. I also use an element of collage, usually toward the end, to disrupt the image and add another element. These come from photos I've taken, part of a series of archival prints I’ve made from my collection of artifacts, textiles, and beadwork from South Africa and the U.S.

I always work on multiple paintings at once, moving back and forth between them. I try not to let a painting arrive too quickly. When I begin, I often sit quietly in front of the blank paper, emptying myself of preconceived ideas, delving into the compost of my being, trying to enter a hallucinatory space where images can surface from somewhere deeper than my conscious mind. This allows me to tap into something more surprising. Something unknown.

Like the other paintings in this series, Woven 12 and 13 arrived slowly, built through repetition, layering, revisions, and decisions that created a rhythm, a structure and a sense of history. That history remains partially visible, shaping the final face of the painting and building its anatomy.

When this work is complete I have to uninstall and reinstall it for photographs and for mounting to panel. This work was created on two separate strips of acetate, so I match them up each time I put the work up. See a photo here:

At one point, in Woven 13, something enticed me: a figure looking at another figure through bars, with a distant landscape in the top right. I liked the space and the texture of sand in the yellow ochre figure against the washes of blue. Visitors to the studio responded to the figurative aspect and the repetition of the yellow ochre “body.” But it felt too easy to read. I needed to complicate it and move beyond preciousness.

I often think about maps: weather patterns, shifting terrains and how they register change, trace movement, and reveal what’s usually unseen. That sense of constant motion - of systems unfolding over time and space - feels deeply connected to the evolution of a painting. In Woven 13, I added a wash of pink as a contrast, knowing it might create a problem, but also knowing problems move me forward. A saturated yellow arch in Woven 12 helped disrupt the initial harmony and add another level of space and dimension.

Collaging photographic fragments, cut from larger images, abstracts the segment by removing the context and shifting the original meaning. Placing them in multiple areas before settling, looking for a sense of dislocation, and adding another element to complicate the ease of the painting.

In these two paintings, I also wanted the collage segment to integrate into the painted surface almost seamlessly, leading to a quiet dislocation. This sense of fragments being removed from one place and absorbed into another opened new relationships in the work. Adding problems keeps the process active and the search alive. Each layer takes me deeper into my core.

Still, something didn’t sit right. I turned the paintings upside down to eliminate the figurative read. I'm not interested in something familiar, but rather something that lives on the edge of consciousness. That shift helped. I adjusted the collage fragment. In Woven 13, I washed over the pink and added repetition of lines, working between them so it became unclear which mark came first, which space was background, which foreground.

Eventually, after long pauses and returns and working on other pieces, the works arrived where abstraction and representation wove together. Woven 12 and 13 live between those states, woven from personal and cultural threads. I am interested in how different visual languages can inhabit the same space - sometimes with friction, sometimes with connection. They become a weaving of self and story, an attempt to make sense through form, to hold memory, movement, belonging, and the layered questions of identity.

The Irish writer and poet Samuel Beckett once wrote that the artist’s quest is to rid himself of extraneous knowledge in order to refine perception into a clear, distilled vision of inner being. That resonates with me. In making these paintings, I discovered something more elusive, something I hadn’t seen before, but recognized when it finally emerged.